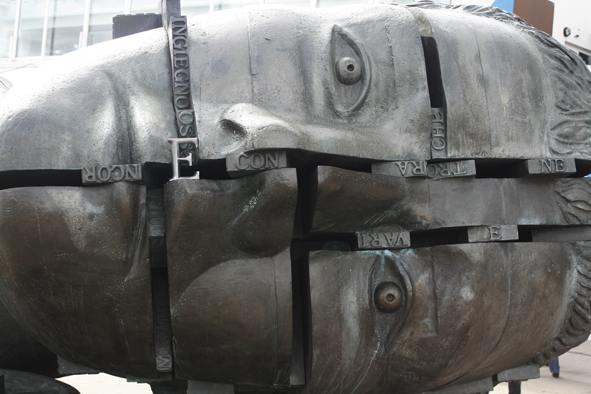

When I interviewed the artist Colin Moore, a few weeks ago. I asked him about a painting of his that I liked called DEATH AND THE FISHERMAN. He said this painting - along with another painting NO MORE FISHING - were a sort of statement about social awareness on the state of the declining fishing industry. He also talked about the towns where fishing was once so important and where so many people were employed, yet now was no more. Less fish in the sea, less fisherman, and more and more rules governing exactly how you should fish, what sort of fish you can catch and the quantities you're allowed to catch etc, all featured in his discussion.

|

| DEATH AND THE MAIDEN OVER - MYCHAEL BARRATT DEATH AND THE FISHERMAN - COLIN MOORE |

These paintings, by two very gifted and talented artists, inspired me to do my own version of death turning up, where he is not wanted! I have called my work DEATH AND THE COAL MINER. I have tried to do something a little different to get the effect I wanted.

Firstly, the subject came from the fact my mum - who is now 88 - came from a coal-mining village, called Dipton, which is just outside Newcastle. My grandad, whom I never met, was a miner. From what I understand, many people from these small communities, earned their livelihood from the local coal pit; there was little opportunity for work, other than the local coal mine.

I then went to my local wood yard and bought two off-cuts, from railway sleepers, which I had sliced into wooden bricks. The wood represents the old wooden struts, which supported the old coal mining tunnels. Having the wood cut into bricks represents the dismantling of the coal industry in Britain. I have used black paint, only, to represent the coal itself and the darkness of deep coal mining. Also, the blackness of the face of the coal miner, after he had finished his shift.

Death represents the thousands who have lost their lives, or who have been terribly injured in the industry. The hourglass represents time running out for the coal miner. Before the famous year-long strike in 1984/85, there were 200 pits, employing 200,000 people. Now there are about 12, employing 8,000.

Death represents the thousands who have lost their lives, or who have been terribly injured in the industry. The hourglass represents time running out for the coal miner. Before the famous year-long strike in 1984/85, there were 200 pits, employing 200,000 people. Now there are about 12, employing 8,000.

It wasn't easy to paint on the bricks. I had to rub each one down with sandpaper, but it gave the effect I wanted. Also, by moving the bricks around, I found that it helped to form shadows, which I believe add to the overall effect.

The following week after completing the work I found an old wooden fire place that had just been dumped in a back street of SE1. I went back with my car to pick it up with the help of Judith my long suffering wife and took it home. With the old fire place I made a frame for Death and the Coal Miner to fit into. Which was great because it had another link with coal. I kept the wood just as it was, rough and ready, but again it added to the over all effect.

During my research, I found this poem, written over 120 years ago, about a mining accident in Glamorganshire. It is a long poem, but if you can read it all, I am sure you will be moved by it.

During my research, I found this poem, written over 120 years ago, about a mining accident in Glamorganshire. It is a long poem, but if you can read it all, I am sure you will be moved by it.

THE PIT OF DEATH

Morfa, Glamorganshire. 10th. March 1890

There was five of us in the gall'ry, all huddled against a wall,

In the terrible silence that followed the rush and the roar and the fall.

Not a muscle moved amongst us - not a sound, not a sigh, not a breath,

For we knew that there in the darkness we were face to face with Death!

Ah, God! the terrible silence that came when the noise was done,

With a thousand feet of earth 'twixt us and the blessed sun:

And the willing hands and hearts three days from us and life,

And kiss the little children, and "Thank God!" of the sore-tried wife.

I spoke in the gruesome darkness, "Mates, be you all alive?"

"Aye," says one and another, until I had counted five.

And the last spoke I knew: "Father! I'm here; it's me!

And I'm not afraid to die, if only I die with thee!"

'Twas my youngest lad, My Davy, too bright, too young to die.

I lifted my hand in the darkness and found him standing by.

"Davy," I said, "who knows? mayhap we'll be saved all right,

And see thy mother and sisters, and thank God with 'em tonight.

Then Morgan spoke in a whisper, as men will speak in Church -

Low and solemn, and awe-struck: "They surely will start a search,

And make for us quick as they can; but, lass it'll not be to-day;

The gallery's fallen in, and we're more than a mile away!"